Next: Radiative Transfer

Up: Physical Background

Previous: Stellar Wind

Contents

Virial Analysis

For a system to achive a mechanical equlibrium,

a relation must be satisfied

between energies such as potential, thermal and kinetic energies.

This is called the Virial relation.

For example, a harmonic oscillator

has

a potetial energy of

has

a potetial energy of

and a kinetic energy

and a kinetic energy

.

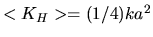

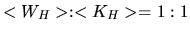

Averaging these two energies over one period,

both energies give the same absolute value proportional to the oscillation

amplitude

.

Averaging these two energies over one period,

both energies give the same absolute value proportional to the oscillation

amplitude  squared as

squared as

and

and

.

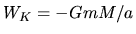

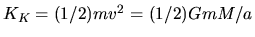

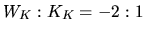

Another example is a Kepler problem.

For simplicity, consider mass

.

Another example is a Kepler problem.

For simplicity, consider mass  running

on a circular orbit with a radius

running

on a circular orbit with a radius  from a body with a mass

from a body with a mass  .

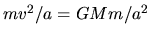

The gravitational and kinetic energies are equal to

.

The gravitational and kinetic energies are equal to  and

and

, where we used the centrifugal balance

as

, where we used the centrifugal balance

as

.

As a result,

for the harmonic oscillator

.

As a result,

for the harmonic oscillator

while for the circular

Kepler problem

while for the circular

Kepler problem  .

This ratio is known to be related to the power

.

This ratio is known to be related to the power  of

the potetial as

of

the potetial as

.

Important nature of the self-gravity is understood only with this relation

without solving the hydrostatic balance equations.

In the following, we describe the Virial relation satisfied with isolated

systems such as stars.

.

Important nature of the self-gravity is understood only with this relation

without solving the hydrostatic balance equations.

In the following, we describe the Virial relation satisfied with isolated

systems such as stars.

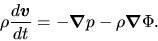

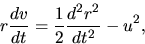

Hydrodynamic equation of motion using the Lagrangean time derivative [eq.(A.3)] is

|

(2.104) |

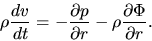

For simplicity, consider a spherical symmetric configuration.

The equation of motion is expressed as

|

(2.105) |

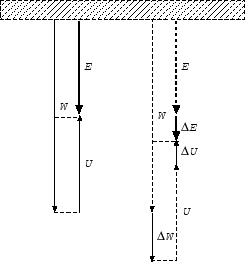

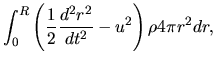

Multiplying radius  to the equation

and integrating by the volume

to the equation

and integrating by the volume  over a volume

from

over a volume

from  to

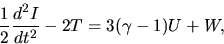

to  , we obtain the Virial relation as

, we obtain the Virial relation as

|

(2.106) |

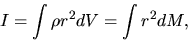

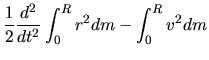

where

|

(2.107) |

is an inertia of this body,

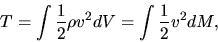

and  and

and  are, respectively, the kinetic and thermal energies as

are, respectively, the kinetic and thermal energies as

|

(2.108) |

|

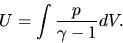

(2.109) |

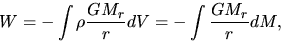

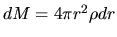

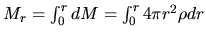

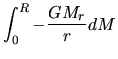

Further,

|

(2.110) |

is a gravitational energy, where

and

and

Since

|

(2.111) |

the lefthand-side of equation (2.105) is rewritten as

using equations (2.107) and (2.108).

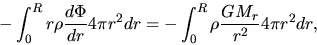

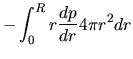

On the other hand, the first term of the rhs of equation (2.105)

becomes

To derive this equation, we have assumed the pressure diminishes

at a radius  and the surface pressure term does not appear in the

final expression.

This is valid for an isolated system such as a star.

and the surface pressure term does not appear in the

final expression.

This is valid for an isolated system such as a star.

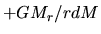

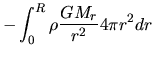

The last term of the rhs of equation (2.105) is written as

|

(2.114) |

wher we used equation (2.13).

This is rewritten as

The energy  per unit mass is necessary for a gas element

to move from the radius

per unit mass is necessary for a gas element

to move from the radius  , inside which mass

, inside which mass  is contained, to the

infinity.

Adding the energy

is contained, to the

infinity.

Adding the energy  for all the gas,

the potential energy is obtained.

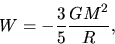

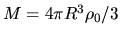

In the case of a star composed of uniform density

for all the gas,

the potential energy is obtained.

In the case of a star composed of uniform density  ,

,

|

(2.116) |

where

.

.

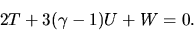

To obtain a condition for the mechanical equilibrium, we assume  .

Equation (2.106) becomes

.

Equation (2.106) becomes

|

(2.117) |

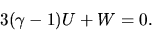

Assuming the stystem is static  , the above equation reduces to

, the above equation reduces to

|

(2.118) |

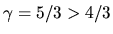

In the case of  this reduces to

this reduces to  .

The total energy

.

The total energy  is expressed as

is expressed as

For the gas with  , equation (2.119) gives

a negative total energy

, equation (2.119) gives

a negative total energy  and the system is in a confined state.

However, if

and the system is in a confined state.

However, if  , the gravity can not confine the gas.

, the gravity can not confine the gas.

For

, equation (2.118) gives

, equation (2.118) gives

|

(2.120) |

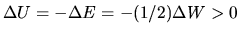

This shows us a strange nature of the self-gravitating gas (see Fig. 2.10).

That is, if the heat flux flows outward, the total energy decreases

.

The system must contract and equation (2.119)

indicates

.

The system must contract and equation (2.119)

indicates

(the gravitational energy decreases:

the absolute value of the gravitational energy increases).

However, for the thermal energy,

equation (2.120) indicates that

(the gravitational energy decreases:

the absolute value of the gravitational energy increases).

However, for the thermal energy,

equation (2.120) indicates that

for this system to be static.

This shows that if the heat flux flows out from the system

the thermal energy increases in the self-gravitating system.

This comes from the contraction due to the gravity.

for this system to be static.

This shows that if the heat flux flows out from the system

the thermal energy increases in the self-gravitating system.

This comes from the contraction due to the gravity.

Figure 2.10:

Virial relation for stars composed of  gas.

gas.

|

Next: Radiative Transfer

Up: Physical Background

Previous: Stellar Wind

Contents

Kohji Tomisaka

2007-11-02

![]() has

a potetial energy of

has

a potetial energy of

![]() and a kinetic energy

and a kinetic energy

![]() .

Averaging these two energies over one period,

both energies give the same absolute value proportional to the oscillation

amplitude

.

Averaging these two energies over one period,

both energies give the same absolute value proportional to the oscillation

amplitude ![]() squared as

squared as

![]() and

and

![]() .

Another example is a Kepler problem.

For simplicity, consider mass

.

Another example is a Kepler problem.

For simplicity, consider mass ![]() running

on a circular orbit with a radius

running

on a circular orbit with a radius ![]() from a body with a mass

from a body with a mass ![]() .

The gravitational and kinetic energies are equal to

.

The gravitational and kinetic energies are equal to ![]() and

and

![]() , where we used the centrifugal balance

as

, where we used the centrifugal balance

as

![]() .

As a result,

for the harmonic oscillator

.

As a result,

for the harmonic oscillator

![]() while for the circular

Kepler problem

while for the circular

Kepler problem ![]() .

This ratio is known to be related to the power

.

This ratio is known to be related to the power ![]() of

the potetial as

of

the potetial as

![]() .

Important nature of the self-gravity is understood only with this relation

without solving the hydrostatic balance equations.

In the following, we describe the Virial relation satisfied with isolated

systems such as stars.

.

Important nature of the self-gravity is understood only with this relation

without solving the hydrostatic balance equations.

In the following, we describe the Virial relation satisfied with isolated

systems such as stars.

![$\displaystyle -\left\{\left[4\pi r^3 p\right]_0^R -3\int_0^R 4\pi r^2 p dr \right\},$](img578.png)

![]() .

Equation (2.106) becomes

.

Equation (2.106) becomes

![]() , equation (2.118) gives

, equation (2.118) gives